Revisiting the 1986 Wapping dispute brought back no sense of journalistic achievement. As one of the labour and industrial correspondents who reported the strike by 5,500 sacked printworkers, my abiding recollection is one of failure.

I fear my coverage on BBC Radio did not get across the full magnitude of the brutality and potential implications of Rupert Murdoch’s covert decision to switch production of his newspapers from Fleet Street to what became known as Fortress Wapping.

Memories of the challenges we journalists faced came flooding back when listening online to a symposium marking the 40th anniversary of the dispute which was held at Marx Memorial Library in Clerkenwell.

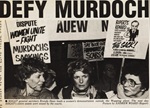

Two of the sacked workers, print trade union officials and sympathetic observers described what they were convinced was a pincer movement against their fight to defend jobs.

Murdoch was accused of being in league with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the Metropolitan Police, backed by the national news media, with the BBC, “a propaganda arm of the government”, falling into line.

In so many ways the 13-month strike by News International’s print workers mirrored the agonies of the preceding 1984-85 miners’ strike and the failure of the mining communities to stop pit closures.

Like the National Union of Mineworkers, the two main print unions, National Graphical Association and Society of Graphical and Allied Trades, retained great confidence in their industrial strength, which had proved so decisive in the past.

They believed – as they continued to demonstrate night after night – that eventually the might of their mass picketing would succeed in halting Murdoch’s new printing presses and in forcing the management and government to backdown.

From the start the prospects looked bleak. Four months into the miners’ strike – especially after the brutal, medieval like scenes at the Battle of Orgreave – the police were effectively in control.

Their ruthless crackdown had effectively corralled the miners’ pickets at pitheads across the coalfields, expertise which two years later would ensure free passage for the TNT lorries leaving Wapping to distribute copies of The Sun, News of the World, The Times and Sunday Times.

My assessment in June 1986, in an article for The Listener, was that six months into the Wapping dispute the print unions needed to change tactics if they were to have any hope of winning over wider public support.

I had formed the same view in the summer of 1984 when reporting the miners’ strike. I thought the NUM would have had a greater chance of putting pressure on Mrs Thatcher if they had done more to publicise the plight of the strikers’ families.

Broadcasters were not welcome in the mining communities, and such was the NUM’s hostility towards the BBC and national newspapers, that journalists were often rebuffed when seeking to report first hand on the extent of the suffering.

Street collections for the strikers and their families were just one indication of the deep well of sympathy for the coalfield communities. The challenge for the NUM’s leadership was to find ways to leverage that concern to exert political pressure on Mrs Thatcher.

I think she would have been vulnerable if the NUM had weaponised the hardship of the families rather than devote so much of their fund-raising towards financing the expense of daily picketing at the pitheads.

That same blinkered approach bedevilled the leadership of the print unions. As I wrote in The Listener (5.6.1986) the printworkers’ fight against Murdoch had one unique characteristic: the public were not merely innocent bystanders, powerless to respond, as was so often the case in industrial disputes.

“On this occasion, over four and a half million people who buy The Sun and The Times (plus another six million on Sunday) were exercising their choice each day of the week by purchasing one of Murdoch’s newspapers.

“Therefore, the print unions did have an opportunity to inflict real damage on News International if sufficient readers could have been persuaded to buy alternative newspapers.”

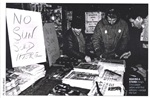

Illustrating my report was a photograph of a lone news vendor at King’s Cross Station selling the first editions of next day’s newspapers with handwritten signs on his stall declaring “No Sun sold here”.

On some Saturday mornings at Watford (a town with a strong affinity with the printing trade) a printworker paraded outside the main newsagent’s shop with a “Don’t buy” poster.

“If there had been national co-ordination behind such protests, with printworkers parading throughout the country, this might have had far more impact on the public than a mass picket late each Saturday night at Wapping.”

Statistics from the Audit Bureau of Circulation underlined my sad conclusion over the lack of imaginative thinking by the union leadership about the potential damage they could achieve by promoting a boycott.

After some initial disruption and a slight dip in sales in the first weeks of the dispute, ABC figures showed The Sun sold 4.3 million copies a day in March, up by 250,000 on the month before the move to Wapping.

As a participant in the Wapping symposium pointed out, given the experience in Liverpool, a boycott might well have been a powerful weapon.

To this day, die-hard supporters of Liverpool FC still refuse to buy or even read The Sun in a continuing protest at the false accusation by the infamous Sun editor Kelvin MacKenzie that they were to blame for the 1989 Hillsborough disaster.

A front-page report titled “The Truth” accused the fans of urinating and obstructing police who were trying to help the dying.

Symposium speaker Morag Livingstone, author and documentary filmmaker, acknowledged the effectiveness of the Liverpool boycott. Organising a protest like that within a community could have a far greater impact than could have been achieved nationally.

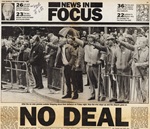

She thought the print unions were at a disadvantage during the Wapping dispute because they had no influence over the news agenda as dictated by the national newspapers, reflecting their hostility towards the strike.

Amid mounting anger and frustration as the dispute continued, the sacked workers had no hesitation about who was to blame.

Journalists and broadcasters like me were criticised for failing to report the “real facts” and for not “telling the truth” about what was happening on the picket lines at Wapping.

Half a dozen journalists from The Times had joined the strike from the start, becoming celebrated Refuseniks, but in the opinion of the “inkies” membership of the National Union of Journalists was no advantage as it only provoked fresh taunts of us being members of the “National Union of Judases”.

There was little or no recognition or understanding within the union hierarchy of the sense of weariness in newsrooms about a daily roundup about picketing and the dilemma over how much space and time to devote to such reports.

To the strikers’ dismay, unless there had been a major disturbance, all that tended to be considered newsworthy was a line or two about the number of arrests or the extent of any injuries, prompting the inevitable accusation that the media were only interested in reporting violence.

In the first two weeks of the strike there was a major missed opportunity to capture the news agenda after a highly damaging revelation.

Farrer & Co, the Queen’s solicitors, had advised News International that the “cheapest way” to dispense with their workforce was to dismiss their employees while they were “participating in a strike or other industrial action”.

Here was a headline-grabbing story which helped to explain the extent of the subterfuge and deceit behind Murdoch’s mass sacking, a dramatic disclosure tailor-made for a carefully timed news conference to exploit peak-time radio and television bulletins and programmes.

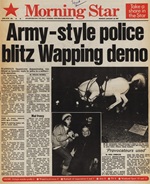

A leaked copy of Farrer’s letter had been passed to Mick Costello, industrial correspondent for the Morning Star, which splashed on the story under the headline, “Dirty war plans exposed: Murdoch caught red handed”. (4.2.1986)

Costello’s exclusive earned the admiration of fellow journalists and was widely praised by the print unions, but I found BBC newsrooms and programme editors somewhat wary about giving the leak the prominence it deserved.

Their concern reflected unease over the Morning Star’s association with the Communist Party and the circumstances surrounding the leak.

Costello quite rightly refused to give me any indication of his source. He denied it had been supplied by the unions.

Three days later the NGA leader Tony Dubbins appeared to confirm the unions had been the source, referring in a signed article in The Guardian to “the letter we revealed this week from Murdoch’s lawyers”.

Dubbins did not comment on the failure of the unions to do more to exploit the leak. On reflection, perhaps I should have – and could have – done more to try ensure it received greater traction on the BBC.

Farrer & Co were certainly relieved at the apparent inability of the NGA and SOGAT to maximise what could have been damaging publicity.

One senior partner later confided their surprise at the way they had escaped so lightly.

If the unions’ objective had been to try to persuade the public not to buy The Sun or The Times, then maximum impact was needed early in the morning.

If breakfast-time radio and television programmes had been invited to a 7.30am news conference at which the SOGAT leader Brenda Dean intended to make “a major announcement about the involvement of the Queen’s solicitors in the Murdoch dispute”, there might even have been live coverage.

Miss Dean could easily have asked listeners and viewers to think carefully about the newspaper they intended to purchase that morning. With a little advance planning, her appeal could have been backed up by printworkers parading outside news agents.

At the Wapping symposium, the Morning Star’s editor Ben Chacko, described the paper’s pride in having been “the only newspaper to stand shoulder to shoulder with the workers of Wapping”.

He said Farrer’s letter had been passed to Costello by another journalist, and he thought his paper’s scoop 40 years ago had exposed how Murdoch had used the introduction of new technology at Wapping as “an excuse to get rid of his workforce and disempower the print unions”.

The two sacked workers, John Lang and Paul King, who were handed dismissal letters within half an hour of the dispute starting, told the symposium that so much was stacked against them.

They and their colleagues did all they could get people interested in the strike but the image in the national news media that they were all “greedy print workers” was difficult to overcome.

Granville Williams, long-standing member of the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom – and editor of Media North – feared that a lasting consequence of News International’s move to Wapping was that it reinforced a culture among Murdoch’s journalists of taking risks and breaking the law.

Print unions and their members had been a powerful force in supporting press freedom.

“Unions in the newspaper industry were a safeguard against many of the abuses which have become commonplace since Wapping, intrusion into privacy, phone hacking and a more aggressive right-wing style of journalism.”

Illustrations: Morning Star, 26.1.1987; The Sun, 27.1.1986; The Sun, 14.2.1986; Sunday Times, 8.6.1986; Morning Star, 4.2.1986; The Sun, 6.2.1987.