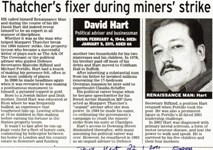

David Hart, a shadowy financier who secretly helped the working miners to start crippling legal action against the National Union of Mineworkers, had almost unlimited access to Margaret Thatcher during the 1984-5 pit strike.

David Hart, a shadowy financier who secretly helped the working miners to start crippling legal action against the National Union of Mineworkers, had almost unlimited access to Margaret Thatcher during the 1984-5 pit strike.

But in the final month of the dispute the Prime Minister was advised to sever her contacts with Hart because news of his role was leaking out and on the point of becoming an embarrassment to the government.

Behind the scenes Hart was passing on instructions to the National Coal Board’s chairman Ian MacGregor and this had angered the Secretary of State for Energy, Peter Walker, who complained to Mrs Thatcher.

Walker’s disagreements with MacGregor over his management of the way the Coal Board was dealing with the strike became increasingly acrimonious after acceleration in the return to work.

At one point the Energy Secretary wrote to Mrs Thatcher accusing MacGregor of being “dishonest” in his pursuit of a vendetta against NACODS, the union for pit safety supervisors.

But it was the Prime Minister’s encouragement for the secret activities of the working miners’ shadowy Mr Fixit that prompted Walker’s first complaint.

In a note dated 27 February 1985, her political secretary Stephen Sherbourne advised Mrs Thatcher to consider “how we sever the link with David Hart in a way which is clear to him but does not unduly offend him.”

In a note dated 27 February 1985, her political secretary Stephen Sherbourne advised Mrs Thatcher to consider “how we sever the link with David Hart in a way which is clear to him but does not unduly offend him.”

Sherbourne accused Hart of pursuing his own agenda and of getting involved in other sensitive issues, such as seeking to become a “go between” in negotiations between the UK and the USA over a possible American “Star Wars” missile shield.

In an attempt to pacify Walker, she assured the Energy Secretary that Hart had no “informal, official or unofficial” position in Downing Street and that at no point had she or No 10 authorised Hart to pass on instructions to MacGregor.

Nonetheless Mrs Thatcher’s letter did acknowledge that Hart had “at times provided useful and accurate information” about secret support for the working miners in the Nottinghamshire coalfield and their challenge to the leadership of the NUM.

The moves to persuade Mrs Thatcher to distance herself from Hart are revealed in her 1985 cabinet papers. His persistence in ringing the Prime Minister direct at either Downing Street or Chequers had clearly annoyed her private office, which considered Hart was exploiting his No 10 connections for his own ends at the expense of the government.

Hart had been advised in future to speak first to one of the private secretaries and then only if he was “really concerned about developments in the coal talks”. But such was his determination to speak to Mrs Thatcher herself that he might well ring her direct at Chequers that weekend.

The cabinet papers reveal that early in February 1985, as the return to work was gathering pace, Hart advised Mrs Thatcher to adopt “tough measures to force men” back to the pits.

“I agree there are considerable political dangers. But the greater danger is prolonging the strike beyond the tolerance of the public.”

Hart’s note to the Prime Minister coincided with a last-minute attempt by the TUC General Secretary Norman Willis to see if an agreement could be reached between the union and management.

The NCB’s insistence that any settlement would require “written confirmation” from the NUM that it would eventually accept the board’s right to manage the industry was welcomed by Hart.

“Any backing-down from this position could be fatal to the outcome of the dispute and would be seen as a defeat for you personally since you have clearly underlined the need for written assurances from the union.

“It would also have a detrimental effect on the pound. Any weakening of resolve would be seen by the international financial community as a sign that you had lost your grip on affairs or else that the country was ungovernable.”

Hart advised Mrs Thatcher on the proposal by the South Wales coalfield for an orderly return to work to avoid the break-up of the union after the likely humiliation of defeat.

In his opinion, Arthur Scargill was intent on prolonging the dispute indefinitely. While opposing the return to work and insisting the union could continue defying pit closures on a pit by pit basis, the NUM President could at the same argue that if the miners are “starved back to work they have already won because they have managed to stay out for so long.”

Even so Hart believed a return to work by the strikers without an agreement with the NCB remained the most likely outcome and was the best option for the government.

“It will be an unequivocally clear victory...it will bring into stark relief the clear pointlessness of the strike. For the membership of the NUM, for the country, Scargill will be blamed. Scargillism will be discredited. And MacGregor will be able to manage the business and close uneconomic pits.”

However, once the strike collapsed at the end of February, the tension between Walker and MacGregor re-surfaced and their relationship reached breaking point when the chairman began to force through pit closures and speed up the rate of redundancy.

In a letter to the Prime Minister on 9 May 1985, Walker said MacGregor was failing to meet his target for reducing manpower from 171,000 to 140,000 by March 1988. “I am far from satisfied with his performance.”

Walker also claimed that MacGregor had “conceded too much” in October 1984 to prevent NACODS joining the NUM strike. He feared there could be fresh industrial action because the union had decided to hold another ballot in protest at what the supervisors believed were violations in the agreement on pit closures after the concessions they had won the previous year.

“We have a rather uncertain personality guiding events at present. He has an impossibly large task as chairman and chief executive of a demoralised, ineffective organisation. I believe we need to appoint one or two new deputy chairmen from June, despite the risk that MacGregor will disagree and that he could take this to its ultimate conclusion and resign.”

Later in the month, after the coal board warned that NACODS’ overtime ban could result in men losing their incentive bonuses and holiday pay, Walker said that was no justification for this “particularly tough attitude” as it fuelled the concern within the NACODS leadership that MacGregor was out to “get his own back...and try to destroy their union.”

At the top of Walker’s letter claiming that MacGregor’s conduct would “once again be looked upon as a dishonest act,” there was a note from Mrs Thatcher saying, “We cannot let this go on”.

Illustrations:Independent 9 May 1994; Daily Express 22 January 2012